Tasmanian Aborigines

| Regions with significant populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Languages | |||

|

Tasmanian languages and Palawa kani |

The Tasmanian Aborigines (pronounced /æbɵˈrɪdʒɨniːz/ (![]() listen), Aboriginal name: Palawa) were the indigenous people of the island state of Tasmania, Australia.

listen), Aboriginal name: Palawa) were the indigenous people of the island state of Tasmania, Australia.

Prior to British colonisation in 1803, there were an estimated 2,000–8,000 Palawa. A number of historians point to introduced disease as the major cause of the destruction of the full-blooded Aboriginal population.[1][2][3][4] Geoffrey Blainey wrote that by 1830 in Tasmania: “Disease had killed most of them but warfare and private violence had also been devastating.”[5] Other historians regard the Black War as one of the earliest recorded modern genocides.[6] Benjamin Madley wrote: “Despite over 170 years of debate over who or what was responsible for this near-extinction, no consensus exists on its origins, process, or whether or not it was genocide.” [7]

By 1833, George Augustus Robinson, sponsored by Lt.Governor George Arthur, had persuaded the approximately 200 Tasmanian Aborigines survivors to surrender themselves with assurances that they would be protected and provided for. These 'assurances' were in fact lies - promises made to the survivors that played on their desperate hopes for reunification with lost family and community members. The assurances were given by Robinson solely to remove the Aborigines from mainland Van Diemen's Land. [8] The survivors were moved to Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island, where diseases continued to reduce their numbers even further. In 1847, the last 47 living inhabitants of Wybalenna were transferred to Oyster Cove, south of Hobart, on the main island of Tasmania. There, perhaps[9][10] the very last of the full blooded Palawa, a woman called Trugernanner (often rendered as Truganini), died in 1876.

All of the Indigenous Tasmanian languages have been lost. Currently there are some efforts to reconstruct a language from the available wordlists. Today, some thousands of people living in Tasmania and elsewhere can trace part of their ancestry to the Palawa, since a number of Palawa women were abducted, most commonly by the sealers living on smaller islands in Bass Strait; some women were traded or bartered for; and a number voluntarily associated themselves with European sealers and settlers and bore children. Those members of the modern-day descendant community who trace their ancestry to Tasmanian Aborigines have mostly European ancestry, and did not keep the traditional Palawa culture.

Other Aboriginal groups within Tasmania use the language words from the area where they are living and/or have lived for many generations uninterrupted. Many aspects of the Aboriginal Tasmanian culture are continually practised in various parts of the state and the islands of the Bass Strait.

Contents

|

History

Before European settlement

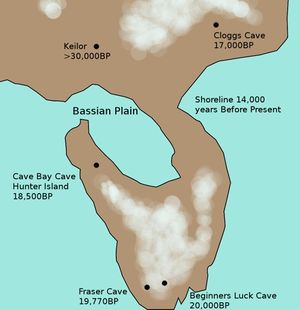

People are thought to have crossed into Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago via a land bridge between the island and the rest of mainland Australia during the last glacial period. According to genetic studies, once the sea levels rose flooding the Bassian Plain, the people were left isolated for approximately 8,000 years until European exploration during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[11]

In the Warreen Cave in the Maxwell River valley of the south-west archaeologists have recently excavated materials proving Aboriginal occupation from as early as 35,000 BP, making indigenous Tasmanians the southern-most population in the world during the Pleistocene era.

After the sea rose to create Bass Strait, the Australian mainland and Tasmania became separate land masses, and the Aborigines who had migrated from mainland Australia became cut off from their cousins on the mainland. Because neither side had ocean sailing technology, the two groups were unable to maintain contact.

It has been a long held view that unlike other populations around the world, the small population of Tasmania was not able to share any of the new technological advances being made by mainland groups, thus making Tasmanian Aborigines the simplest people on Earth.[12]

It had also been thought that because of the ocean divide, they did not share any of the mainland Aboriginal advances such as barbed spears, bone tools of any kind, boomerangs, hooks, sewing, and the ability to start a fire.[12] However, they did possess fire with the men entrusted in carrying embers from camp to camp for cooking and which could also be used to clear land and herd animals to aid in hunting practices.[13][14]

It has been suggested that approximately 4,000 years ago, the Tasmanian Aborigines largely dropped scaled fish from their diet, and began eating more land mammals such as possums, kangaroos, and wallabies. They also switched from worked bone tools to sharpened stone tools.[14] The significance of the dissapearance of bone tools (believed to be primarily used for fishing) and fish in the diet is heavily debated. Some argue that it is evidence of a maladaptive society while others argue that the change was economic as large areas of scrub at that time were changing to grassland providing substantially increased food resources. Fish were never a large part of the diet, ranking behind shellfish and seals, and with more resources available the cost/benifit ratio of fishing may have become too high.[15]

It is now believed that they also constructed basic wooden shelters and small domed 'huts' to protect themselves during chilly winter months, although it seems they preferred to live in cave dwellings.[13]

Very little is known about the nature of social, cultural, or territorial history of the Tasmanian Aborigines, but archaeological research has provided ethnographic evidence debunking many long held myths about Tasmanian Aborigines.

Tasmanian Aboriginal Tribes

The social organisation of Tasmanian Aborigines had three distinct levels: the domestic unit or family group, the social unit or band which had a self-defining name with 40 to 50 people, and collections of bands comprising tribes which owned territories. Even though territories were owned there was substantial movement and migration by bands to utilise and share abundant food resources in particular seasons.[16]

Estimates made of the combined population of the Aboriginal people of Tasmania, prior to European arrival in Tasmania, are in the range of 2,000 to 8,000 people.[17] Genetic studies have suggested much higher figures. Using archaeological evidence, Stockton (I983:68) estimated 3,000 to 6,000 for the northern half of the west coast however, he later revised this to 3,000 to 5,000 for the entire island based on historical sources. The low rate of genetic drift indicates that Stockton's original estimate is likely the lower boundary and, while not indicated by the archaeological record, a population as high as 100,000 can "not be rejected out of hand". This is supported by carrying-capacity data indicating greater resource productivity in Tasmania than the mainland.[11]

The Tasmanian Aborigines were a primarily nomadic people who lived in adjoining territory, moving from area to area based on seasonal changes in food supplies such as seafood, land mammals and native vegetables and berries. The different tribes shared similar languages and culture. They socialized, intermarried and fought 'wars' against other tribes.[13]

There were at least 50 bands prior to European colonisation, although only 48 have been located and associated with particular territories. Nine tribes were composed of three to ten bands each. The Eastern and northern Group consisted of the Oyster Bay Tribe, North East Tribe, and the North Tribe. the Midlands Group consisted of the Big River Tribe, North Midlands Tribe and Ben Lomond Tribe. The Maritime Group consisted of the North West Tribe, South West Tribe and South East Tribe.[16]

Oyster Bay (Paredarerme)

The Paredarerme tribe was estimated to be the largest Tasmanian tribe with 10 bands totalling 700 to 800 people. The Paredarerme Tribe had good relations with the Big River tribe, with large congregations at favoured hunting sites inland and at the coast. Generally Paredarerme tribe bands migrated inland to the High Country for Spring and Summer and returned to the coast for Autumn and Winter, but not all people left their territory each year with some deciding to stay by the coast. Migrations provided a varied diet with plentiful seafood, seals and birds on the coast, and good hunting for kangaroos, wallabies and possums inland. The High Country also provided opportunities to trade for ochre with the North-west and North people, and to harvest intoxicating gum from Eucalyptus gunnii, found only on the plateau.[16]

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Leetermairremener | St Patricks Head near St Marys | Large Congregations in winter before heading inland late October to spend summer in the high country around Ben Lomond and North Midlands |

| Linetemairrener | North Moulting Lagoon north of Great Oyster Bay | Large Congregations in winter before heading inland late October to spend summer in the high country around Ben Lomond and North Midlands |

| Loontitetermairrelehoinner | North Oyster Bay | Large Congregations in winter before heading inland late October to spend summer in the high country around Ben Lomond and North Midlands |

| Toorernomairremener | Schouten Passage | Large Congregations in winter before heading inland late October to spend summer in the high country around Ben Lomond and North Midlands |

| Poredareme | Little Swanport | Winter on the coast before heading west to the Eastern Marshes, and through St Peters pass to Big River Country before returning to the coast in Autumn. |

| Laremairremener | Grindstone Bay | Winter on the coast before heading west to the Eastern Marshes, and through St Peters pass to Big River Country before returning to the coast in Autumn. |

| Tyreddeme | Maria Island | Winter on the coast before heading west to the Eastern Marshes, and through St Peters pass to Big River Country before returning to the coast in Autumn. |

| Portmairremener | Prosser River | Winter on the coast before heading west up the Prosser River to the Eastern Marshes, and through St Peters pass to Big River Country before returning to the coast in Autumn. |

| Pydairrerme | Tasman Peninsula | Winter on the coast before heading west to the Eastern Marshes, and through St Peters pass to Big River Country before returning to the coast in Autumn. |

| Moomairremener | Pittwater, Risdon | In September moved inland up the Derwent River to Big River Country returning to the midlands in February and the coast by June. |

North East

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Peeberrangner | uncertain | |

| Leenerrerter | uncertain | |

| Pinterrairer | uncertain | |

| Trawlwoolway | uncertain | |

| Pyemmairrenerpairrener | uncertain | |

| Leenethmairrener | uncertain | |

| Panpekanner | uncertain |

North

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Punnilerpanner | Port Sorell | |

| Pallittorre | Quamby Bluff | |

| Noeteeler | Hampshire Hills | |

| Plairhekehillerplue | Emu Bay |

Big River

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Leenowwenne | New Norfolk | |

| Pangerninghe | Clyde - Derwent Rivers Junction | |

| Braylwunyer | Ouse and Dee Rivers | |

| Larmairremener | West of Dee | |

| Luggermairrernerpairrer | Great Lake |

North Midlands

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Leterremairrener | Port Dalrymple | |

| Panninher | Norfolk Plains | |

| Tyerrernotepanner | Campbell Town |

Ben Lomond

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Plangermaireener | uncertain | |

| Plindermairhemener | uncertain | |

| Tonenerweenerlarmenne | uncertain |

North West

The North west tribe numbered between 400 and 600 people at time of contact with Europeans and had at least eight bands.[16]

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Tommeginer | Table Cape | |

| Parperloihener | Robbins Island | |

| Pennemukeer | Cape Grim | |

| Pendowte | Studland Bay | |

| Peerapper | West Point | |

| Manegin | Arthur River mouth | |

| Tarkinener | Sandy Cape | |

| Peternidic | Pieman River mouth |

South West Coast

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Mimegin | Macquarie Harbour | |

| Lowreenne | Low Rocky Point | |

| Ninene | Port Davey | |

| Needwonnee | Cox Bight |

South East

| Band | Territory | Seasonal migration |

|---|---|---|

| Mouheneenner | Hobart | |

| Nuenonne | Bruny Island | |

| Mellukerdee | Huon River | |

| Lyluequonny | Recherche Bay |

Early European Contact

Abel Jansen Tasman, credited as the first European to discover Tasmania (in 1642) and who named it Van Diemen’s Land, did not encounter any of the Tasmanian Aborigines when he landed. In 1772, a French exploratory expedition under Marion Dufresne visited Tasmania. At first, contact with the Aborigines was friendly; however the Aborigines became alarmed when another boat was dispatched towards the shore. It was reported that spears and stones were thrown and the French responded with musket fire killing at least one Aborigine and wounding several others. Two later French expeditions led by Bruni d'Entrecasteaux in 1792-93 and Nicolas Baudin in 1802 made friendly contact with the Tasmanian Aborigines; the d'Entrecasteaux expedition doing so over an extended period of time.[18] The Resolution under Captain Tobias Furneaux (part of an expedition led by Captain James Cook) had visited in 1773 but made no contact with the Tasmanian Aborigines although he left gifts in unoccupied shelters found on Bruny Island. The first known British contact with the Tasmanian Aborigines was on Bruny Island by Captain Cook in 1777. The contact was peaceful. Captain William Bligh also visited Bruny Island in 1788 and made peaceful contact with the Tasmanian Aborigines.[19]

Contact with Sealers on the North and East Coasts.

More extensive contact between Tasmanian Aborigines and Europeans resulted when British and American seal hunters began visiting the islands in Bass Strait as well as the northern and eastern coasts of Tasmania from the late 1790s on. Shortly thereafter (by about 1800), sealers were regularly left on uninhabited islands in Bass Strait during the sealing season (November to May). The sealers established semi-permanent camps or settlements on the islands, which were close enough for the sealers to reach the main island of Tasmania in small boats and so make contact with the Tasmanian Aborigines.[20]

Trading relationships developed between sealers and Tasmanian Aboriginal tribes. Hunting dogs became highly prized by the Aborigines, as were other ‘exotic’ items such as flour, tea and tobacco. The Aborigines traded kangaroo skins for such goods. However, a trade in Aboriginal women soon developed. Many Tasmanian Aboriginal women were highly skilled in hunting seals, as well as in obtaining other foods such as sea-birds, and some Tasmanian tribes would trade their services, and more rarely those of Aboriginal men, to the sealers for the seal-hunting season. Others were sold on a permanent basis. This trade incorporated not only women of the tribe engaged in the trade but also women abducted from other tribes. Some may have been given as ‘gifts’ meant to incorporate the new arrivals into Aboriginal society through marriage. Some of the women were taken back to the islands by the sealers involuntarily and some went willingly, as in the case of a woman called Walyer who went with the sealers voluntarily to escape an Aboriginal man who had tried to kill her.[20]

Historian James Bonwick reported Aboriginal women who were clearly captives of sealers but he also reported women living with sealers who 'proved faithful and affectionate to their new husbands', women who appeared ‘content’ and others who were allowed to visit their ‘native tribe’, taking gifts, with the sealers being confident that they would return.[21] Bonwick also reports a number of claims of brutality by sealers towards Aboriginal women including some of those made by George Augustus Robinson.[22]

Sealers also engaged in their own raids along the coasts to abduct Aboriginal women and were reported to have killed Aboriginal men in the process. By 1810 seal numbers had been greatly reduced by hunting so most seal hunters abandoned the area, however a small number of sealers, approximately fifty mostly ‘renegade sailors, escaped convicts or ex-convicts’, remained as permanent residents of the Bass Strait islands and some established families with Tasmanian Aboriginal women.[23]

The raids for, and trade in, Aboriginal women contributed to the rapid depletion of the numbers of Aboriginal women in the northern areas of Tasmania, “by 1830 only three women survived in northeast Tasmania among 72 men” [20] and thus contributed in a significant manner to the demise of the full-blooded Aboriginal population of Tasmania. However many modern day Tasmanian Aborigines trace their descent from the 19th century sealer communities of Bass Strait.

There are numerous stories of the sealers' alleged brutality towards the Aboriginal women; with many of these reports originating from George Augustus Robinson. In 1830, Robinson seized fourteen Aboriginal women from the sealers, planning for them to marry Aboriginal men at the Flinders Island settlement. Josephine Flood, an archaeologist specialising in the Australian Aboriginal peoples, notes: “he encountered strong resistance from the women as well as sealers”. The sealers sent a representative, James Munro, to appeal to Governor Arthur and argue for the women’s return on the basis that they wanted to stay with their sealer husbands and children rather than marry Aboriginal men unknown to them. Arthur ordered the return of some of the women.

Shortly thereafter, Robinson began to disseminate stories, supposedly told to him by James Munro, of atrocities allegedly committed by the sealers against Aborigines and against Aboriginal women, in particular.

Archaeologist Josephine Flood argues: “The sudden appearance of such tales precisely when he wanted to blacken the sealers' reputation is highly suspicious and it seems inconceivable that Munro would have told Robinson such self-incriminating stories. The final reason for rejecting these lurid tales as untrue is their uncanny resemblance to a volume of horror stories by Bartolemé de las Casas, intended to condemn Spaniards in the Americas!” The las Casas stories and those told by Robinson about the Bass Strait sealers “all have similar features - seizing children and killing them before their mothers` eyes, cutting flesh off living people and making them eat it, feeding people to dogs, cutting off victims' hands, cannibalism, emasculation, rape, ripping open pregnant women or burning people alive. Plomley, who edited Robinson's papers, expressed scepticism about these atrocities in lengthy annotations. It is also significant that no such tales were reported to Archdeacon Broughton's 1830 committee of inquiry into violence towards Tasmanians. Abduction and ill-treatment of Aborigines certainly occurred, but the extent of atrocities and 'massacres' has been grossly exaggerated.”[24]

After European Settlement

Between 1803 and 1823, there were two phases of conflict between the Aborigines and the British colonists. The first took place between 1803 and 1808 over the need for common food sources such as oysters and kangaroos, and the second between 1808 and 1823, when the small number of white females among the farmers, sealers and whalers, led to the trading, and the abduction, of Aboriginal women as sexual partners. These practices also increased conflict over women among Aboriginal tribes. This in turn led to a decline in the Aboriginal population. Historian Lyndall Ryan records seventy-four Aborigines (almost all women) living with sealers on the Bass Strait islands in the period up to 1835.[25]

Archaeologist Josephine Flood argues that there is no evidence of the widespread kidnapping of Aboriginal children as labourers that some historians have claimed. A small number of young Aboriginal children were known to be living with settlers; twenty-six were definitely known (through baptismal records) to have been taken into settlers' homes as infants or very small children, too young to be of service as labourers. Some Aboriginal children were sent to the Orphan School in Hobart.[26] Lyndall Ryan reports fifty-eight Aborigines, of various ages, living with settlers in Tasmania in the period up to 1835.[27]

Some historians argue that European disease did not appear to be a serious factor until after 1829.[28] Other historians including Geoffrey Blainey and Keith Windschuttle, point to introduced disease as the main cause of the destruction of the full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginal population. Keith Windschuttle argues that while smallpox never reached Tasmania, respiratory diseases such as influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis and the effects of venereal diseases devastated the Tasmanian Aboriginal population whose long isolation from contact with the rest of humanity compromised their resistance to introduced disease. The work of historian James Bonwick and anthropologist H. Ling Roth, both writing in the 19th century, also point to the significant role of epidemics and infertility without clear attribution of the sources of the diseases as having been introduced through contact with Europeans. Bonwick, however, did note that Tasmanian Aboriginal women were infected with venereal diseases by Europeans. Introduced venereal disease not only directly caused deaths but, more insidiously, left a significant percentage of the population unable to reproduce. Josephine Flood, archaeologist, wrote: "Venereal disease sterilised and chest complaints - influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis - killed." [29][30]

Bonwick, who lived in Tasmania, recorded a number of reports of the devastating effect of introduced disease including one report by a Doctor Story, a Quaker, who wrote: “After 1823 the women along with the tribe seemed to have had no children; but why I do not know.”[31] Later historians have reported that introduced venereal disease caused infertility amongst the Tasmanian Aborigines.[32][33]

Bonwick also recorded a strong Aboriginal oral tradition of an epidemic even before formal colonisation in 1803. “Mr Robert Clark, in a letter to me, said : “I have gleaned from some of the aborigines, now in their graves, that they were more numerous than the white people were aware of, but their numbers were very much thinned by a sudden attack of disease which was general among the entire population previous to the arrival of the English, entire tribes of natives having been swept off in the course of one or two days illness.” “ [1] Such an epidemic may be linked to contact with sailors or sealers.[34]

Henry Ling Roth, an anthropologist, wrote: “Calder, who has gone more fully into the particulars of their illnesses, writes as follows....: “Their rapid declension after the colony was founded is traceable, as far as our proofs allow us to judge, to the prevalence of epidemic disorders….””[35] Roth was referring to James Erskine Calder who took up a post as a surveyor in Tasmania in 1829 and who wrote a number of scholarly papers about the Aborigines. "According to Calder, a rapid and remarkable declension of the numbers of the aborigines had been going on long before the remnants were gathered together on Flinders Island. Whole tribes (some of which Robinson mentions by name as being in existence fifteen or twenty years before he went amongst them, and which probably never had a shot fired at them) had absolutely and entirely vanished. To the causes to which he attributes this strange wasting away ... I think infecundity, produced by the infidelity of the women to their husbands in the early times of the colony, may be safely added. . . . Robinson always enumerates the sexes of the individuals he took; . . . and as a general thing, found scarcely any children amongst them; . . . adultness was found to outweigh infancy everywhere in a remarkable degree. . . ."[36]

George Augustus Robinson recorded in his journals a number of comments regarding the Tasmanian Aborigines’ susceptibility to diseases, particularly respiratory diseases. In 1832 he revisited the west coast of Tasmania, far from the settled regions, and wrote: "The numbers of aborigines along the western coast have been considerably reduced since the time of my last visit [1830]. A mortality has raged amongst them which together with the severity of the season and other causes had rendered the paucity of their number very considerable." [37]

Rapid pastoral expansion and an increase in the colony's population triggered Aboriginal resistance from 1824 onwards. Whereas settlers and stock keepers had previously provided rations to the Aborigines during their seasonal movements across the settled districts, and recognised this practice as some form of payment for trespass, the new settlers and stock keepers were unwilling to maintain these arrangements.

While many aboriginal deaths went unrecorded the Cape Grim massacre in 1828 demonstrates the level of frontier violence towards Tasmanian aborigines.

The Aborigines began to raid settlers' huts for food. This resistance first took shape in 1824 when it has been estimated by Lyndall Ryan that 1000 Aborigines remained in the settled districts.

Between 1826 and 1831 a pattern of guerrilla warfare by the Aborigines was identified by the colonists, some of whom acknowledged the Aborigines as fighting for their country. The colonial government responded with a series of measures to limit the conflict, culminating in the declaration of martial law in 1828.

The Black War of 1828-32 and the Black Line of 1830 were turning points in the relationship with European settlers. Even though the tribes managed to avoid capture during these events, they were shaken by the size of the campaigns against them, and this brought them to a position whereby they were willing to surrender to Robinson and move to Flinders Island.

George Augustus Robinson, a Christian missionary, befriended Truganini, learned some of the local language and in 1833 managed to persuade the remaining "full-blooded" people to move to a new settlement on Flinders Island, where he promised a modern and comfortable environment, and that they would be relocated to the Tasmanian mainland as soon as possible.

At the Wybalenna Aboriginal establishment on Flinders Island, described by historian Henry Reynolds as the ‘best equipped and most lavishly staffed Aboriginal institution in the Australian colonies in the nineteenth century’,[38] they were provided with housing, clothing, rations of food, the services of a doctor and educational facilities. Convicts were assigned to build housing and do most of the work at the settlement including the growing of food in the vegetable gardens. The Aborigines were free to roam the island and were often absent from the settlement for extended periods of time on hunting trips.[39] However, of the 220 who arrived with Robinson, most died in the following 14 years from introduced disease. The birth rate was extremely low with few children surviving infancy.

In October 1847, the 47 survivors were transferred to their final settlement at Oyster Cove, where their numbers continued to diminish.[40] In 1859 their numbers were estimated at around a dozen; the last survivor died in 1876.

Anthropological interest

The Oyster Cove people attracted contemporaneous international scientific interest from the 1860s onwards, with many museums claiming body parts for their collections. Scientists were interested in studying Tasmanian Aborigines from a physical anthropology perspective, hoping to gain insights into the field of paleoanthropology. For these reasons, they were interested in individual Aboriginal body parts and whole skeletons.

Tasmanian Aboriginal skulls were particularly sought internationally for studies into craniofacial anthropometry.

In one case, the Royal Society of Tasmania received government permission to exhume the body of Truganini in 1878 on condition that it was "decently deposited in a secure resting place accessible by special permission to scientific men for scientific purposes." Her skeleton was on display in the Tasmanian Museum until 1947.[41]

Other cases included the removal of the skull and scrotum — for a tobacco pouch — of William Lanne, known as King Billy, on his death in 1869. Truganini, the last Tasmanian Aborigine, had her skeleton exhumed within 2 years of her death in 1876 by the Royal Society of Tasmania, and was later placed on display.

Aborigines have considered the dispersal of body parts as being disrespectful, as a common aspect within Aboriginal belief systems is that a soul can only be at rest when laid in its homeland.

20th century to present day

Body parts and ornaments are still being returned from collections today, with the Royal College of Surgeons of England returning samples of Truganini's skin and hair (in 2002); and the British Museum returning ashes to two descendants in 2007.[42]

During the 20th century, the absence of "full blood" Palawa and a general unawareness of the surviving populations, mean that many non-Palawa assumed they were extinct, after the death of Truganini in 1876. Since the mid 1970s Tasmanian Aboriginal activists such as Michael Mansell have sought to broaden awareness and identification with Aboriginal descent.

There is a dispute within the Tasmanian Aboriginal community over what constitutes Aboriginality. A group that identifies itself as the Lia-Pootah claim to be descendants of Tasmanian Aboriginal women, many of whom had been abducted and had children with European sealers that worked in the Bass Strait in the nineteenth century. The Lia Pootah feel that the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre represent the Palawa politically but not the Lia Pootah.[43]

More recently there have been initiatives to introduce DNA testing to establish family history in descendant subgroups. This has drawn an angry reaction from some quarters, as some have claimed "spiritual connection" with aboriginality distinct from, but not as important as the existence of a genetic link.[44] The Tasmanian Palawa Aboriginal community is also making an effort to reconstruct and reintroduce a Tasmanian language, called palawa kani out of the various records on Tasmanian languages. Other Tasmanian aboriginal communities use words from traditional Tasmanian languages, according to the language area they were born or live in.

Legislated definition

In June 2005, the Tasmanian Legislative Council introduced an innovated definition of aboriginality into the Aboriginal Lands Act[45]. The bill was passed to allow Aboriginal Lands Council elections to commence, after uncertainty over who was 'aboriginal', and thus eligible to vote.

Under the bill, a person can claim "Tasmanian Aboriginality" if they meet the following criteria:

- Ancestry

- Self-identification

- Community recognition

Government compensation for "Stolen Generations"

On 13 August 1997 a Statement of Apology (specific to removal of children) was issued - which was unanimously supported by the Tasmanian Parliament - the wording of the sentence was

That this house, on behalf of all Tasmanian(s)... expresses its deep and sincere regret at the hurt and distress caused by past policies under which Aboriginal children were removed from their families and homes; apologises to the Aboriginal people for those past actions and reaffirms its support for reconciliation between all Australians.

There are many people currently working in the community, academia, various levels of government and NGOs to strengthen what has been termed as the Tasmanian Aboriginal culture and the conditions of those who identify as members of the descendant community.

In November 2006 Tasmania became the first Australian state or territory to offer financial compensation for the Stolen Generations, Aborigines forcibly removed from their families by Australian government agencies and church missions between about 1900 and 1972. Up to 40 Tasmanian Aborigine descendants are expected to be eligible for compensation from the $5 million package.[46]

Some notable Tasmanian Aborigines

- Trugernanner (Truganini) and Fanny Cochrane Smith, who both claimed to be the last "full blooded" Palawa.

- William Lanne or "King Billy"

Literature

- The play The Golden Age by Louis Nowra

- The novel English Passengers by Matthew Kneale

- Historical novel Doctor Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World by Mudrooroo

- The poem Oyster Cove by Gwen Harwood

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bonwick, James: Daily Life and Origins of the Tasmanians, Sampson, Low, Son and Marston, London, 1870, p84-85

- ↑ Bonwick, James: The Last of the Tasmanians, Sampson Low, Son & Marston, London, 1870, p388

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians: Story of the Aboriginal People, Allen & Unwin, 2006, pp 66-67

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803-1847, Macleay Press, 2002, pp 372-375

- ↑ Geoffrey Blainey, A Land Half Won, Macmillan, South Melbourne, Vic., 1980, p75

- ↑ Colin Tatz, With Intent To Destroy

- ↑ http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/522350

- ↑ 'Van Diemen's Land' James Boyce 2009 p.297

- ↑ On the claim, and the other candidates, Suke and Fanny Cochrane Smith, see Rebe Taylor, Unearthed: the Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island,Wakefield Press, 2004 pp.140ff.

- ↑ Lyndall Ryan, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Allen & Unwin, 1996 p.220, denies Truganini was the last 'full-blood', and makes the case for Suke (d.circa 1888)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pardoe, Colin (1991). "Isolation and Evolution in Tasmania". Current Anthropology 32 (1): 1-27.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Jared Diamond. Guns, Germs, and Steel (1999 ed.). Norton. pp. 492. ISBN 0393061310.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Aboriginal Occupation". ABS. March 26, 2008. http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/dc057c1016e548b4ca256c470025ff88/F6FA372655DCC15FCA256C3200241893?opendocument. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lyndall Ryan, pp10-11, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Second Edition, Allen & Unwin, 1996, ISBN 1863739653

- ↑ Manne, Robert (2003). Whitewash. 317-318: Schwartz Publishing. ISBN 0 9750769 0 6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Lyndall Ryan, pp13-44, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Second Edition, Allen & Unwin, 1996, ISBN 1863739653

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803-1847, Macleay Press, 2002, pp 364-372

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians: Story of the Aboriginal People, Allen & Unwin, 2006, pp 58-60

- ↑ Bonwick, James: The Last of the Tasmanians, Sampson Low, Son & Marston, London, 1870, pp 3-8

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians, pp58-60, p 76

- ↑ Bonwick, James: The Last of the Tasmanians, pp 295-297

- ↑ Bonwick, James: The Last of the Tasmanians, pp 295-301

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians, pp 58-60, p 76

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians, p 76

- ↑ Ryan, Lyndall, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Second Edition, Allen & Unwin, 1996, ISBN 1863739653, Appendix p 313

- ↑ Flood, Josephine. The Original Australians, p 77

- ↑ Ryan, Lyndall, The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Second Edition, Allen & Unwin, 1996, ISBN 1863739653, p 176

- ↑ Boyce, James: Van Diemen’s Land, Black Inc, 2008, ISBN 9781863954136, p65

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians, p 77, p 90, 128

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803-1847, Macleay Press, 2002, pp 372-376

- ↑ Bonwick, Last of the Tasmanians, p388

- ↑ Flood, Josephine, The Original Australians, p 90

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, pp 375-376

- ↑ Flood, Josephine: The Original Australians, pp 66-67

- ↑ Roth, Henry Ling, The Aborigines of Tasmania, Second Edition, Halifax (England): F. King & Sons, Printers and Publishers, Broad Street, 1899, p 18

- ↑ Roth, Henry Ling, The Aborigines of Tasmania, 1899, pp 172-173

- ↑ Plomley, N. J. B. (ed), Friendly Mission, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966, at p 695, Robinson writing to Edward Curr, 22 Sept 1832

- ↑ Flood, Josephine, The Original Australians: Story of the Aboriginal People, Allen & Unwin, 2006, p88, citing Reynolds

- ↑ Flood, Josephine, The Original Australians: Story of the Aboriginal People, Allen & Unwin, 2006, p88-90

- ↑ Bonwick, James: The Last of the Tasmanians, p 270-295

- ↑ Trugernanner (Truganini) (1812? - 1876), Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ↑ "Bodies of Knowledge". The Museum. 2007-05-17. No. 2, season 1.

- ↑ "WHO MAKES UP THE TASMANIAN ABORIGINAL COMMUNITY?". Lia Pootah Community. March 26, 2008. http://www.tasmanianaboriginal.com.au. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ Matthew Denholm, "A bone to pick with the Brits", The Australian, February 17, 2007.

- ↑ Tasmanian Legislation - Aboriginal Lands Act 1995

- ↑ STOLEN GENERATIONS PUBLIC RELEASE, Premier Paul Lennon http://www.premier.tas.gov.au/speeches/stolen.html

External links

- Foster, S.G. Contra Windschuttle, Quadrant, March 2003, 47:3

- Records Relating to Tasmanian Aboriginal People from the Archives Office of Tasmania "Brief Guide No. 18"

- Statistics - Tasmania - occupation (from the Australian Bureau of Statistics)

- The Lia Pootah People Home Page

- Historian dismisses Tasmanian aboriginal genocide "myth" (contains edited transcript of 2002 ABC radio interviews by Peter McCutcheon with historian and author Keith Windschuttle and historian and author Henry Reynolds)

- "Native Fiction" a sympathetic New Criterion review of Keith Windschuttle's book casting doubt on a supposed Tasmanian genocide.

- Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR)

- [1] Reconciliation Australia

- 1984 Review of Tom Haydon's documentary "The Last Tasmanian" (1978)

- "Tension in Tasmania over who is an Aborigine" Article from The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper by Richard Flanagan

- A history from the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Transcript of current affairs television program Sunday with Keith Windschuttle, Prof. Henry Reynolds, Prof. Cassandra Pybus, Prof. Lyndall Ryan, and others

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||